The Fragile World of Prince William Sound

The Fragile World of Prince William Sound

This essay appeared in the January 30, 2020 edition of The Anchorage Press. The Fragile World of Prince William Sound explores the work of Rob Campbell, a biological oceanographer based in Cordova, Alaska. For the last decade Campbell has studied the health of a rich ecosystem that is currently in danger. His findings include observations of plankton that are negatively influenced by both warming waters and an increasing lack of available nutrients. The result of this change is an observable shift in plankton species and diminished concentrations of all plankton in the strata of the ocean where fish are most dependent on them. Why does a tiny little creature matter so much?

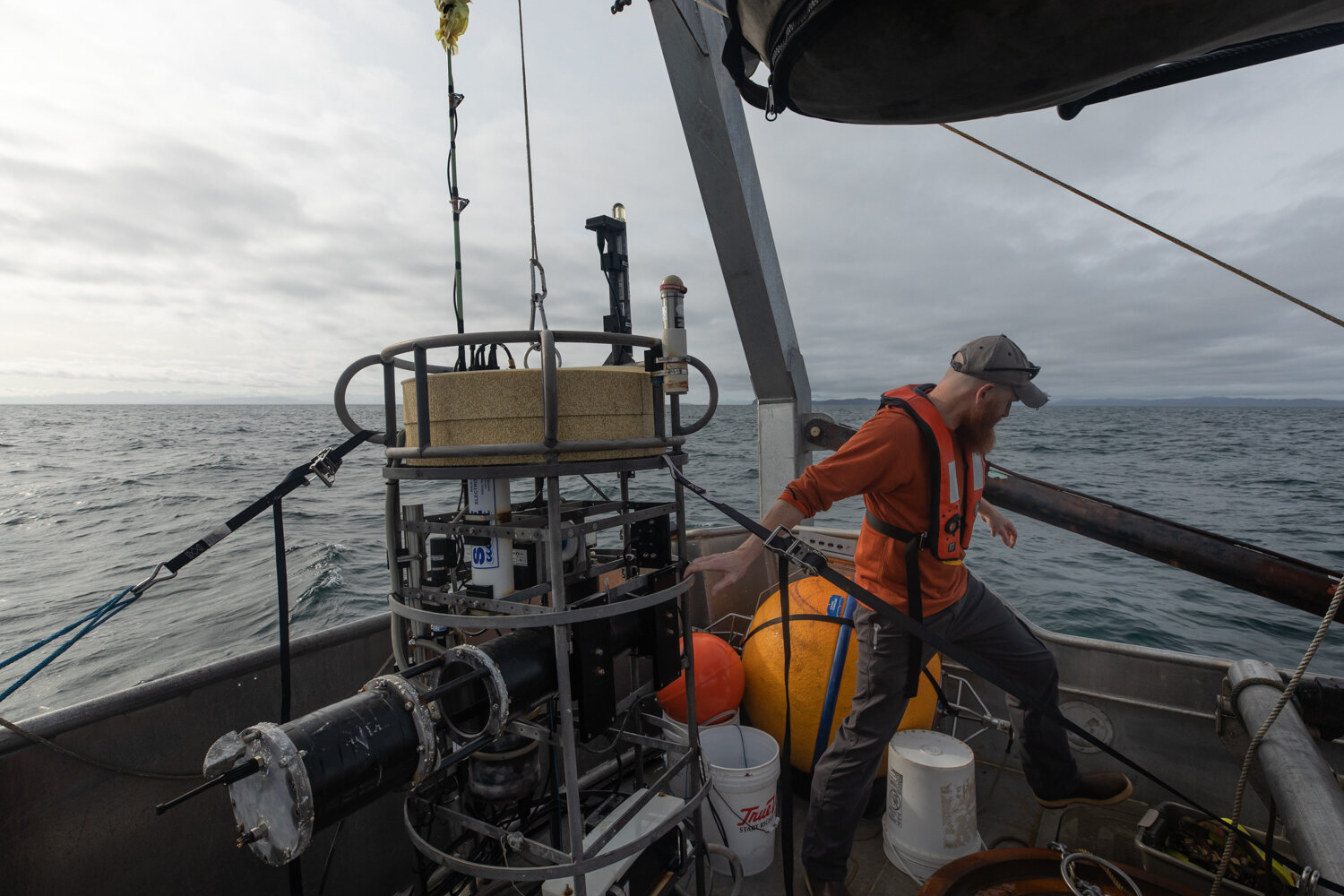

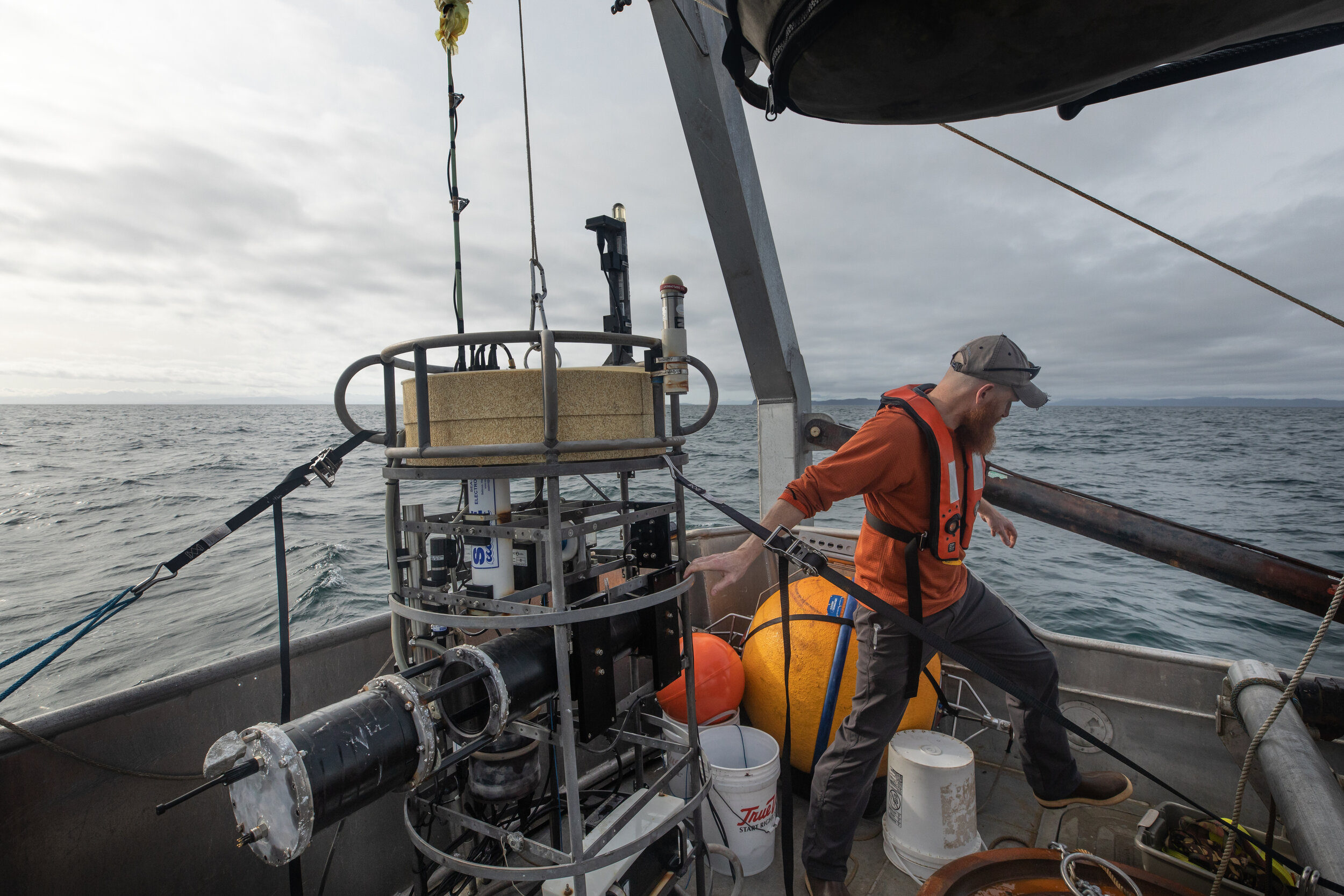

Off the coast of Naked Island, Prince William Sound, Alaska—Rob Campbell deploys an acoustic transmitter, sending signals to a submersible profiler that is several hundred feet underwater. Campbell is a biological oceanographer working for the Prince William Sound Science Center in Cordova, Alaska.

A scientist with a cold beer in his hand, Rob Campbell settled into his Adirondack chair, contemplating the autumn sun from the deck of the Reluctant Fisherman, a popular watering hole above the Cordova boat harbor.

Like other folks living near coastal rainforest, the 47-year-old-oceanographer was more accustomed to precipitation than sunshine, more used to rain-gear than short-sleeves. But last September, as with most of last summer, Alaska experienced record-breaking temperatures, and researchers like Campbell will tell you the heat cuts two ways.

“Marine forecast is calling for two foot seas tomorrow morning and early afternoon,” Campbell told me, “becoming six to eight feet by late afternoon.”

The red-bearded mariner knew I would be with him the following day, on his research vessel, cruising to the center of Prince William Sound where I planned to document his work. And he knew we would likely be motoring back to port in the evening hours, straight into the front of a forecasted storm—something that goes with the territory of his occupation, studying Alaskan waters that are often anything but placid.

Months before I met him in person we first talked on the phone.

“Do you get seasick?” he asked me, an Anchorage based photographer more experienced in the mountains, having just finished a summer full of trips documenting the work of glacier researchers.

In hindsight I realized my answer must have lacked confidence, because the day before our cruise he posed the next logical question.

“Did you bring Dramamine with you?”

“Oh yeah,” I replied, thinking that I definitely don’t have sea legs, and probably never will.

“I suggest you take one tonight and one in the morning,” he said, “because if you wait until it gets rough it will be too late.”

Having some idea what the next day held, I enjoyed the momentary feeling of solid ground, sitting on a deck overlooking the ocean, rather than struggling for equilibrium on a boat deck pitching and rolling in ocean waves.

Among us at the bar sat other Cordova residents, also enjoying the sun, but engrossed in a lively conversation about state politics and the state of commercial fishing. A confabulation ensued, representative of the contentious relationship other Alaskans have with Governor Mike Dunleavy, a classic politician who seems to prefer the bright side of climate change, banking on potential opportunities, rather than preparing for the liabilities. Unsurprising is his alleged position on Pebble Mine, privately supporting a project that’s become a lightning rod for the preservation of salmon and the deeply rooted culture they inspire. Members of our governor’s administration have also suggested that melting glaciers might expose new areas rich in minerals, creating the opportunity for new exploration.

The governor's agenda seems to turn a blind eye to the adversities of warming, and is focused instead on short term goals, some which are understandably aimed at helping a state in fiscal crisis. All that said, it’s always convenient to criticize politicians, much harder to look inward, especially considering how the debate on climate change is often fraught with hypocrisy. But Dunleavy’s motto, Open for Business, seems connected to a mission that pits jobs against the environment. The thing is, history has shown that Alaska can have jobs, even responsible resource extraction, and be conservation minded. After all, the original architects of our state constitution actually wrote in principles aimed not just at utilization, but also conservation and sustainability, largely influenced by concerns about past environmental abuse, including a history of overfishing.

“After all, the original architects of our state constitution actually wrote in principles aimed not just at utilization, but also conservation and sustainability, largely influenced by concerns about past environmental abuse, including a history of overfishing. ”

Alaska’s natural resources were once thought to be endless, a notion rooted in ignorance as much as hubris.

Alaska now faces a different kind of threat. Will it inspire a similar kind of vision that moved state leaders over sixty years ago?

Like much of Alaska and the rest of the country, Cordova is split almost evenly on thorny political issues. What most of the town does agree on is the importance of salmon.

Against the chatter of locals debating politics, Campbell and I discussed the more tangible subject of oceanography.

“Do you know about the thermohaline circulation?” he asked.

The scientist who I assumed was always stoic, suddenly became animated about a subject that revealed his true passion, the often unseen, biological inner workings of the ocean.

Campbell refers to Prince William Sound as the World’s Richest Waters, a maxim he coined that describes the benefits of being next to the North Pacific Ocean, “at the end of a thousand-year-old conveyor belt of ocean currents,” he said, describing the flow of deep salt water that begins its journey from far away, collecting nutrients as the current flows northward, in transit for a millennium before finally arriving at the Gulf of Alaska.

“That conveyor belt is really why we have incredibly productive fisheries here,” Campbell said, referring to the second largest fishery in Alaska.

“The North Pacific is chockablock full of nutrients,” he told me, explaining how “the ocean current gets rained upon with crud the whole time, with organic matter, with dead things, and it all gets rotted by bacteria until all of the nutrients are released.”

Then he nodded toward the Gulf of Alaska, hidden from view by Hawkins and Hinchinbrook Islands.

“By the time it gets a hundred miles over yonder it’s about as nutrient rich as it will get,” he said, referring to the area of ocean between the continental shelf and Prince William Sound. Campbell described the movement of nutrients into coastal Alaskan waters as a “deepwater renewal.”

“In the summer we often get a relaxation in the winds,” he said, “where that water can roll up onto the shelf and all the way into Prince William Sound, leaving hot water sitting on top of cold water,” describing the way temperature and density differentiates sea water, creating stratified layers.

“But then in the winter, storms begin mixing everything up, bringing all those nutrients to the surface,” he explained.

And that’s when Campbell’s excitement slowly turned to unease, when he described the changes he’s seeing.

He explained that our winter storms were once frequent and robust enough to disrupt the relationship between warm and cold water, making nutrients available near the top layer of the ocean. But in the last decade, storm tracks began drifting away from Prince William Sound, a condition that is not definitively linked to climate change, but one that is compounding other changes in a way that makes the cause unworthy of arguing.

Campbell’s work confirms a host of forces that negatively influence plankton in the Sound. Among them, warm and cold water are becoming more stratified, and more resistant to mixing, especially during Spring and throughout the Summer. This results in the top layer of the ocean becoming distinctly separated from the more nutrient rich layer underneath it. In other words, the nutrients are getting partitioned off from the upper layer where plankton feed the most.

“Plankton will almost always use up all the nutrients in the top layer,” he told me, but he’s seeing nutrients in that top layer get exhausted.

“The stronger the density difference between the two layers, the harder it is to disrupt,” he said, clarifying, “when there’s less exchange between the two layers there are fewer nutrients available to plankton each year.”

Referencing Alaska’s longer and hotter summers, and an increasing trend in the rapid melting of alpine glaciers that surround Prince William Sound, Campbell explained, “Adding more heat to the surface of the ocean will tend to enhance stability, as will adding more freshwater.”

“That's what is happening with climate change,” he told me.

The farther the scientist moved into his explanation, the more uneasy he seemed, as if he reached a nebulous point where the implications of his findings diverged from any possible solutions.

So, I asked him, “What are you most concerned about?”

““Temperature,” he answered, unequivocally. The much discussed nexus between the ways of man and our rapidly changing planet. ”

“Temperature,” he answered, unequivocally. The much discussed nexus between the ways of man and our rapidly changing planet.

As a principal investigator working for the Prince William Sound Science Center, last summer Campbell measured temperatures in the Sound that were 7-9 degrees above normal. To put that in perspective, that increase is significantly more detrimental than the same increases of temperature on land.

If warming and negative consequences continue, harvesting fish in parts of Alaska may become untenable in its current form. Adding to that is the concern that hatchery born salmon in Prince William Sound may already be outcompeting native fish, a misunderstood issue that Doug Vincent-Lang, the Commissioner of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, acknowledged in part by stating, “More research is needed.”

But the Commissioner went on to say, “Unfortunately, marine research is costly and in these times of austerity, Alaska has limited resources to assess the changing conditions at sea.” All which is understandable, but in the absence of certainty, and especially in the presence of profound oceanographic changes, maybe additional precaution is needed?

One thing seems certain. In warming waters there will likely be winners and losers, but researchers aren’t yet sure who those will be.

Perhaps the time has come for Alaskans to do some serious soul searching about issues related not just to short term economics, but also long-term sustainability of our fisheries, and even the value of our cultural identity, especially if warming continues as expected. If the effects of warming worsen, or if a profound environmental crisis occurs, it may become a moral conundrum as much as an economic challenge.

As far as Prince William Sound is concerned there’s an emerging problem that can be fundamentally stated: a valuable ecosystem is at risk. This is all the more important because of lingering effects from the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

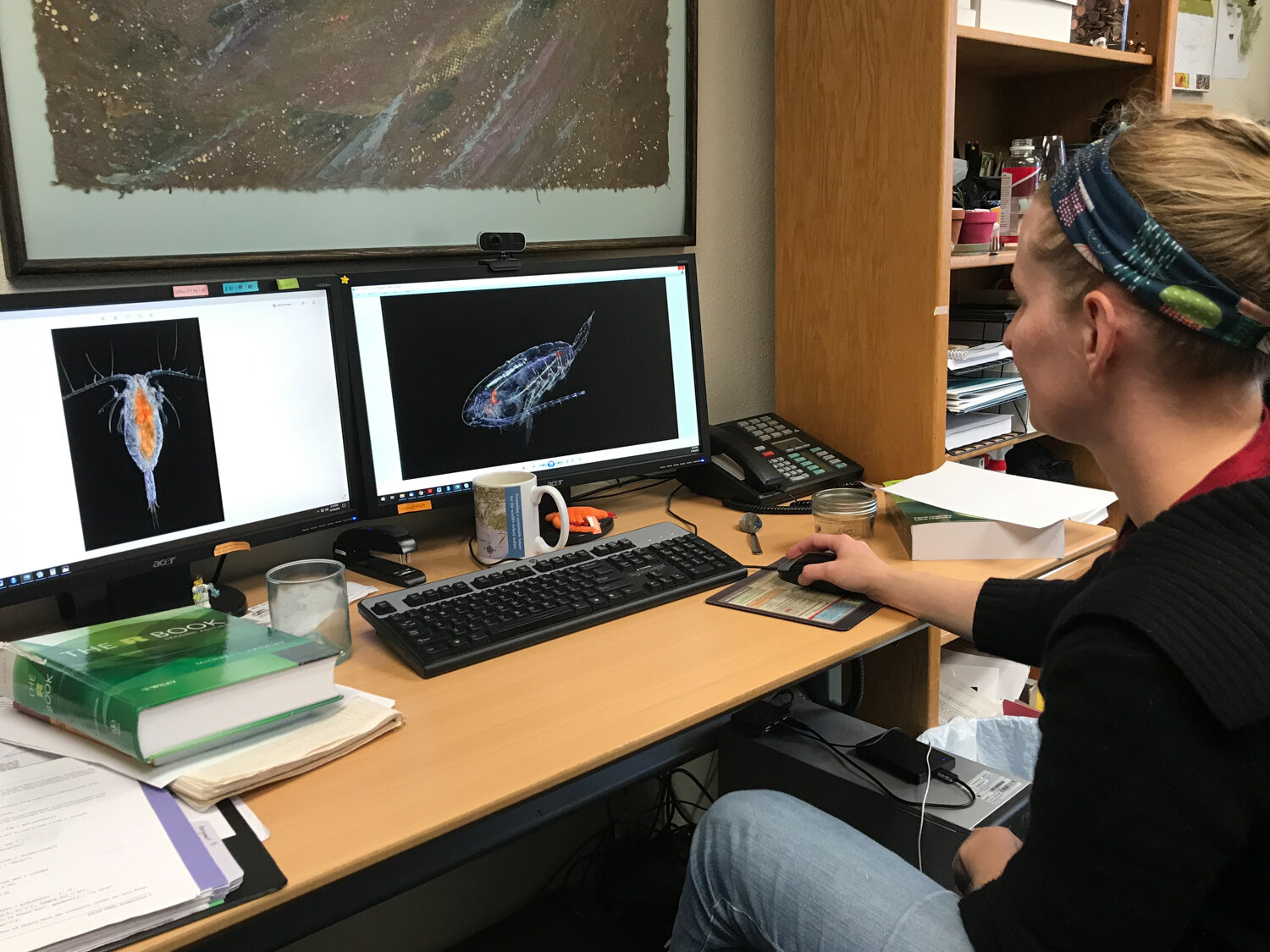

In continuing research, Campbell and another Cordova based biological researcher, Caitlin McKinstry, are observing a shift in the species of plankton in the Sound, from sub-polar plankton, which are larger and filled with more lipids—toward a more subtropical-temperate species, more common in the California Current, and which tend to be smaller bodied and contain fewer lipids.

The end result may be a trend toward fewer nutrients, fewer plankton, and fewer plankton rich in lipids. And that means greater competition for food among ocean dwellers that are dependent on plankton, including salmon.

Regardless of where Cordova residents stand on the political spectrum, when fishing isn’t good the entire town shares the burden. With a population of 2,000 or so, half of the families in town work in careers associated with the sea. This is a place where salt water runs in people’s veins.

With eccentricities you’d expect to find in a small fishing community, Cordova has an intimate feel that belies its enormous surroundings, isolating it geographically from the rest of Alaska, and for that matter the rest of the world. But regardless of its remote position, what happens to Cordova and to Prince William Sound, has wider reaching implications, even suggesting the potential for similar oceanographic changes along the entire northern temperate coastal rainforest.

Just west of Cordova, a convoluted coastline wraps around the immensity of Prince William Sound, a hundred miles wide, with margins interrupted by numerous fjords and river valleys. Connecting her residents with the surrounding sea is the boat harbor, the most iconic fixture in town. And yet, during my time there, the harbor was packed with idling fishing boats during a time when I thought they’d be out fishing.

Campbell told me that most fishermen would ordinarily be gone on a mid-September day, when coho salmon should be heading to their spawning grounds.

Except that last year was full of anything but ordinary days, leaving some of the rivers around Prince William Sound too shallow for salmon to swim into.

When commercial fishermen should have been coming and going at a frenetic pace, working the last opener of the season, instead they were doing maintenance on their boats, waiting for news from state fish managers.

In autumn the average high temperature in Cordova is usually in the mid 50s, but when I was there the mercury sat in the seventies, making the local streams so hot, and shallow, that many salmon were dying before they were able to spawn.

Last summer a number of coastal Alaskan areas experienced an unprecedented drought, leaving some streams bone dry. Other streams were so shallow it forced salmon to spool up in the ocean until finally, they tried entering freshwater, barely inches deep. In some cases thousands of salmon were stranded at a time, the females still full of eggs, slowly suffocating until they died.

Early the next morning we loaded provisions onto the 39-foot research vessel, New Wave, and left the Cordova harbor, headed out for a long day in the middle of Prince William Sound. Besides being a marine scientist, Campbell is also an experienced mariner, and the captain of the vessel belonging to the science center. Along with his partner, McKinstry, the two scientists planned to service a semi-permanent, “autonomous moored profiler” (AMP), that is anchored to the ocean floor. The AMP independently records a variety of measurements on a daily basis, even taking pictures of plankton, that would otherwise require researchers doing numerous surveys out to the ocean.

Getting to the sound first requires threading through a shallow passage where I watched a salmon exit the water, its whole body flying through the air and landing with a big splash. Soon, I realized there were more salmon, as far as I could see, each one punctuating an airborne flight with a big splash.

“Traversing the surface of the ocean evoked a sense of an enigmatic world underneath us, but with inextricable connections to the terrestrial environment above. Two different worlds uniquely mirroring each other. When one environment undergoes dramatic change, so does the other.

”

Traversing the surface of the ocean evoked a sense of an enigmatic world underneath us, but with inextricable connections to the terrestrial environment above. Two different worlds uniquely mirroring each other. When one environment undergoes dramatic change, so does the other.

About three hours later we arrived at an inconspicuous spot somewhere in the center of the Sound, marked only by Campbell’s GPS. He cut the power, putting the giant, twin diesels in idle.

Almost immediately the vessel began rising and falling with each wave, and pitching back and forth like a metronome. Campbell told me it seemed “calm,” oddly suggesting that conditions would not be improving.

I was glad I took the Dramamine.

Campbell placed an acoustic transmitter in the saltwater and began cycling through different frequencies, sending signals to an electronic hitch that anchored the AMP to the ocean floor. The pinging sound was unmistakably iconic, conjuring images of Jacque Cousteau suddenly appearing in his wet suit, wearing his trademark red hat. Waiting for the AMP to appear at the surface, I found myself fascinated with the peculiar romance of marine science.

As if Campbell sensed my daydreaming, he warned me, “no one has gone overboard on the New Wave yet, so please don’t be the first.”

I took his words to heart, quickly learning the art of picture making with a single hand, the other hand planted firmly on anything I could grab.

Watching me struggle for balance, the seasoned mariner shared an apt saying from the book of sailor-isms.

“One hand for yourself, and one for the ship,” he said.

For the next fifteen minutes or so all three of us scanned the choppy seas around us, looking for the AMP.

After it finally appeared, Campbell motored over to it. What followed is best described as comedy, the three of us wrangling a 300 pound device as it dangled on the end of a winch cable over the depths of the ocean. It took several attempts to pull it onto the boat deck, like trying to tame an unwieldy robot, swinging out of unison with the swaying of the boat.

After we finally got the unruly thing on deck, the two scientists quickly strapped it down. Then time was of the essence. Campbell admitted that servicing the AMP rarely ever went smoothly. He would perform routine maintenance and download data from its onboard computer, doing all of that as quickly as possible before the seas got too bad.

The AMP is part of Campbell’s extensive surveys throughout Prince William Sound, trying to assess how the ocean is changing. It broadcasts some data remotely, but stores most of it on its onboard computer that he accesses every 30-45 days.

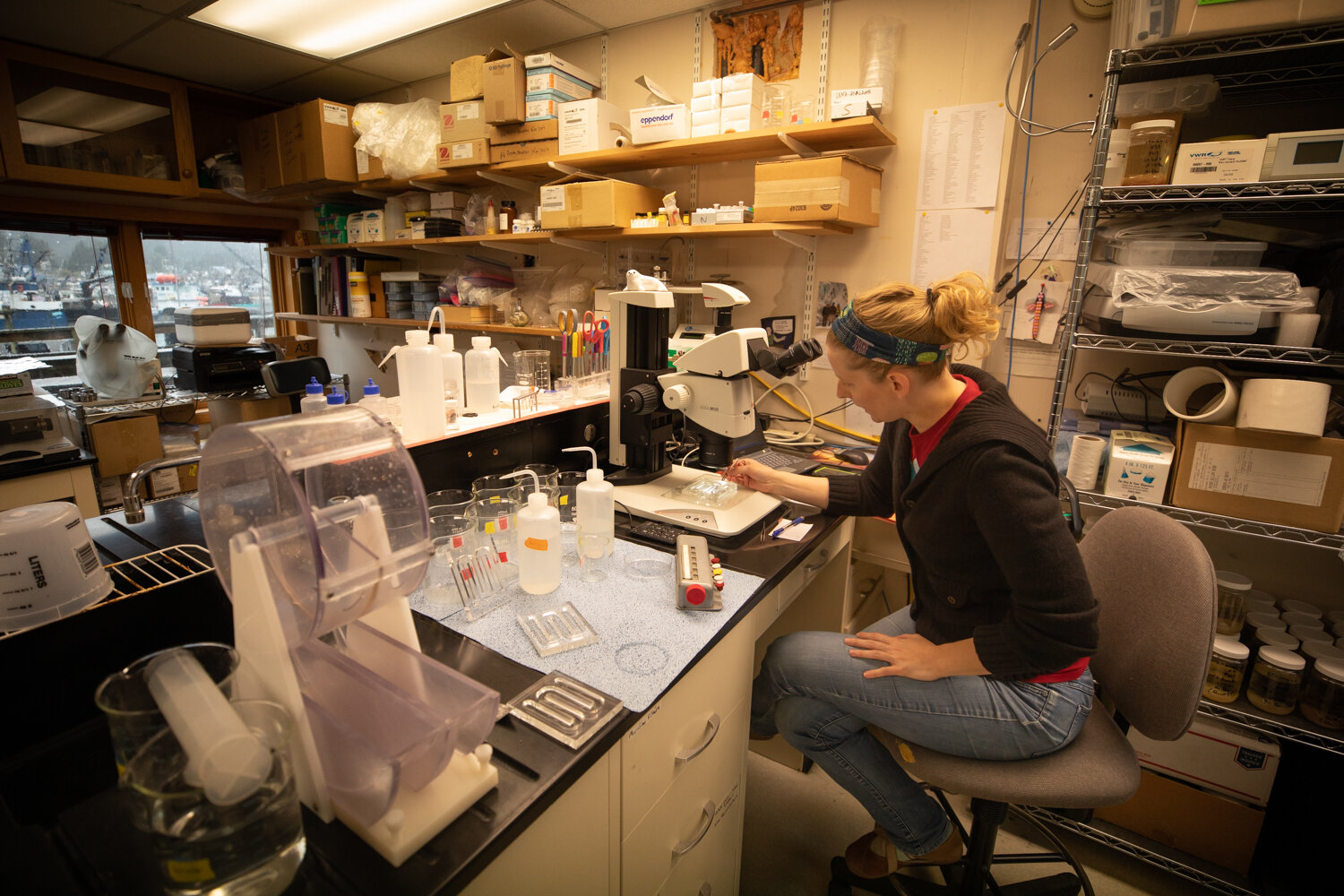

While Campbell worked, McKinstry began taking water samples at prescribed depths, a way to validate what the AMP measured autonomously.

After a few hours Campbell and McKinstry prepared the AMP for redeployment, releasing it back into the ocean to do its work. A heavy anchor quickly pulled it into the depths, hundreds of feet below us.

Afterwards Campbell deployed a uniquely designed plankton net, prompting me to ask, “How many pounds will you be harvesting?”

He laughed out loud, responding, “Not even one!”

“Grams,” he told me, “like a grain of rice or smaller, and they’re mostly water. Just like us.”

I watched him carefully empty the net and fill glass jars with the tiny little creatures, yet they were just big enough that I could see them darting around inside each sample.

“Caitlin pickles them with formaldehyde,” he told me.

“It’s a hundred-year-old technology,” he said, “super old school, but it works.”

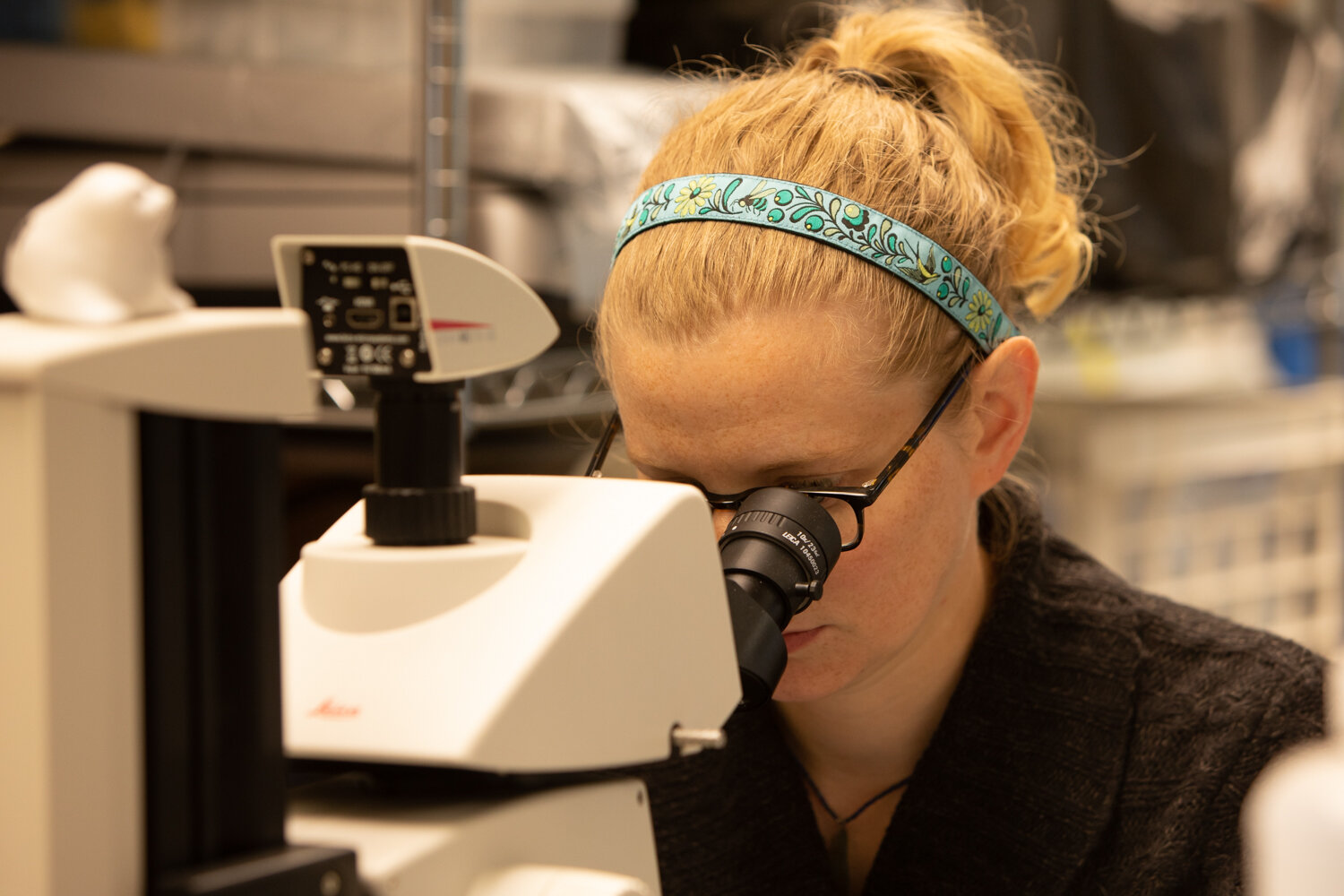

About his partner, he commented, “You need a special personality for microscope work. And Caitlin has that, an attention for detail.”

I joined McKinstry inside the cabin as she labeled and managed a number of different samples on an impressively organized work table. The following day I would visit with her inside her laboratory at the science center, observing as she worked with the microscope. She devised a method for capturing high-resolution images of plankton, resulting in an impressive blend of art and science.

Regardless that the vessel bobbed back and forth, McKinstry seemed adept at getting her work done. As various objects repeatedly slid back and forth across the table, she looked unconcerned, and more focused on the task at hand.

We chatted at length about her work, but she constantly diverted the attention back to Campbell.

“Rob goes to great lengths to validate his measurements,” she commented, “he’s super careful.”

“That’s why we’re collecting all these extra samples,” she explained.

After McKinstry and Campbell finished their final tasks we stowed everything in preparation for a bumpy trip back to Cordova. At first we were under sunny skies, but the leading edge of a big storm loomed ahead of us. Just as Campbell had predicted, the seas got progressively rougher as I watched the bow of the New Wave plowing through wind driven waves. For me it was a white knuckle ride, gripping the edge of my seat every time the vessel lifted out of the water and then dove into the next trough. And yet, Campbell and McKinstry appeared more than relaxed, as if they were content to just be out on the water, no matter the conditions.

About three hours later, as we neared Hawkins Island and the protected bays close to Cordova, the sea suddenly flattened out and I breathed a huge sigh of relief. About twenty minutes later we turned the corner into Orca Inlet, the lights of Cordova coming into sight, and it was then when the sky turned black, and the rain began falling.

Campbell dropped me off at the docks where I unloaded my gear and put on my heavy rain jacket, the first time during my week-long trip. As I walked back toward the Reluctant Fisherman, where I was staying, I realized I’d become accustomed to the sea, at least for a day.

After changing into some street clothes, I went to the bar, sharing it with a few locals, everyone having quiet conversation in the distance. The bartender, a young woman, emanated a perfect blend of moxie and rural attitude.

“Great music tonight,” I said. “Mazzy Star,” she replied. I ordered a beer, all the while listening to apt lyrics, adding to the kind of ambience that only seems to exist in remote places. I sat down next to some big bay windows, overlooking the harbor.

Through the plate glass, I watched a relentless downpour, showcased by long rows of halogen dock lights, each one illuminating the fury of a storm that grew more intense by the hour.

Mesmerized by the force of nature, I lost myself in meandering thoughts, ruminating about my day out on the ocean, learning about an ecosystem that’s invisible to most of us, a world that most of us take for granted, but are happy to reap the benefits from. And learning about a remarkable little creature, holding one of the keys to the health of Prince William Sound. It occurred to me that plankton, although under-appreciated, are just as fundamental to our culture as salmon. Fundamental to a way of life, to livelihoods, and to the health of an interrelated ecosystem.

In some communities, salmon binds people together. Salmon and culture. But salmon live their lives in a world even more mysterious, and maybe even more fragile than ours.

After a few beers, I caught my own reflection on the window next to me, and suddenly felt something luring me outside, as if a mythic siren called me out into the storm. I wanted to feel the rawness of the deluge. So after suiting up with my rain-gear, I ventured out. The sound of the rain overwhelmed my senses, as if the entirety of the ocean was spilling down upon Cordova, signaling a dramatic end to an unprecedented season of heat.

I flew back to Anchorage the next day. And I learned later on that it rained in Cordova for days on end, filling the rivers and streams around Prince William Sound with enough fresh water that some of the late season run of coho salmon could finally go home.